Putting a face to the voice in the head

Voices that insult, harass, control: These are just some of the things patients with auditory hallucinations have to deal with. An innovative virtual reality therapy can help them gain greater control over the voices. The therapy was inspired by computer game technologies.

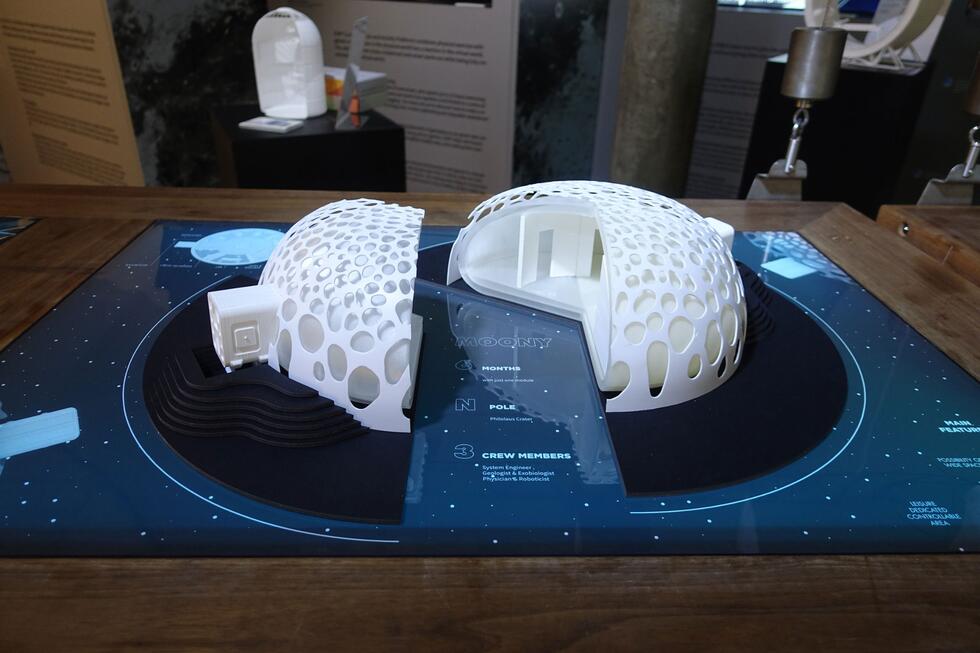

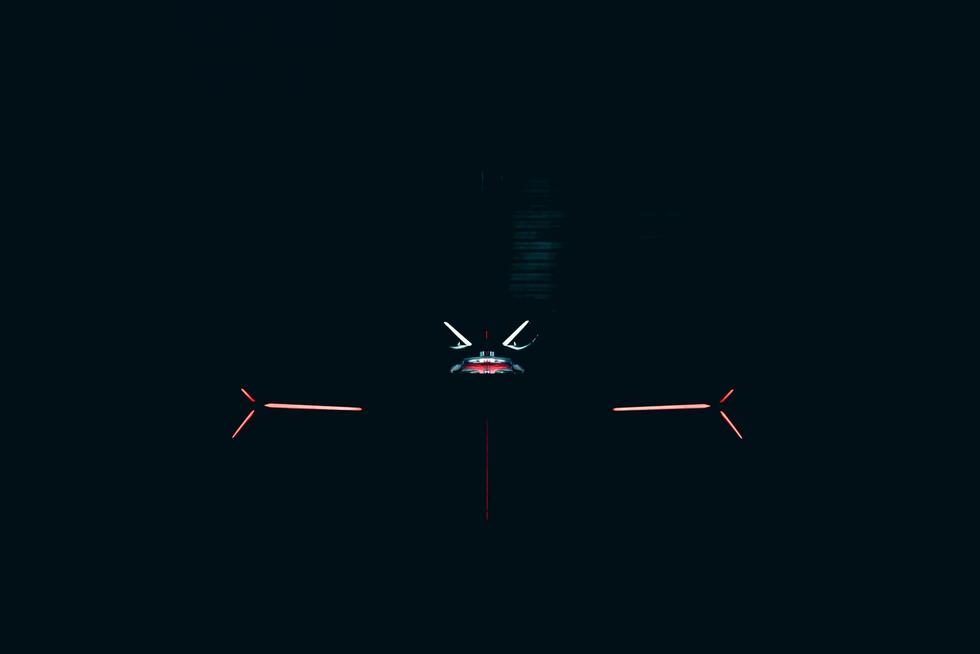

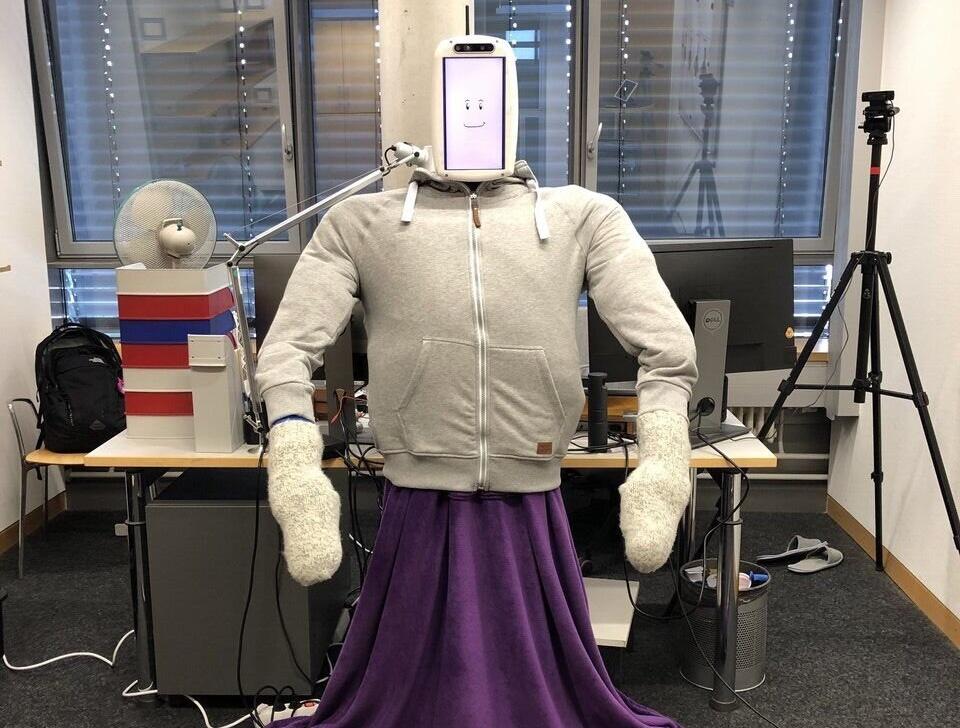

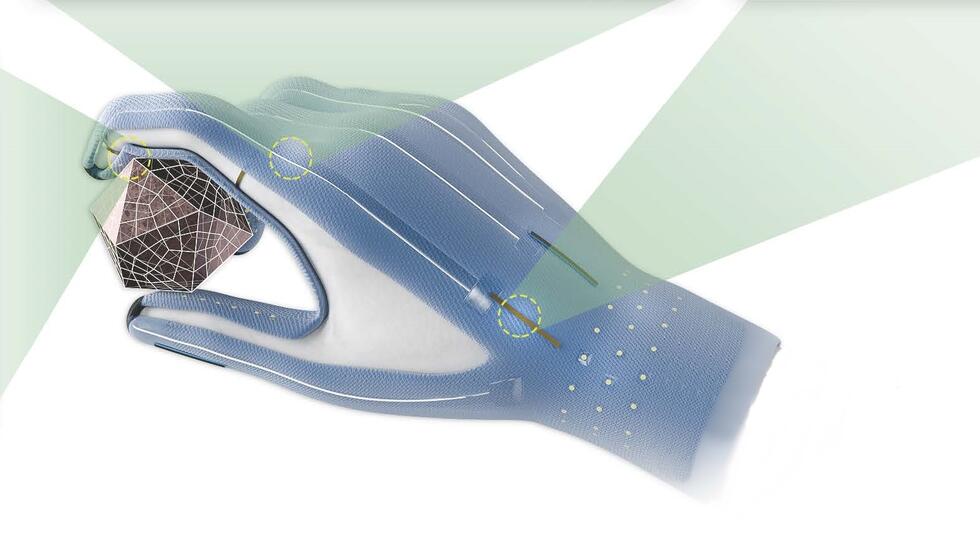

The arms and legs grow thinner the further I move the slider to the right. The avatar on the screen is taking shape. I confirm my choice, click on next, and select: green eyes, purple hair, long beard, shorts, a striped shirt, and no shoes. The avatar is complete. I don the virtual reality goggles and face the character I just created in an inconspicuous but welcoming room. I hear a sonorous “Hello” over the headphones. I can now voice instructions into the microphone: “Look angry.” Immediately, the avatar crosses his arms and furrows his eyebrows.

For me as a journalist, this is just a game. But for the patients at the Center for Integrative Psychiatry (ZIP) at the University Hospital of Psychiatry Zurich, it represents a hope of healing. Here, people who suffer from auditory hallucinations can find treatment. They hear voices that insult, bully, or control them. Such voices can be triggered by various conditions including schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, or depression. As part of the avatar therapy, patients lend a face to the voices in their head. The goal: interact with the voice, become more self-confident, and gain control over it.

Information technology opens up new possibilities

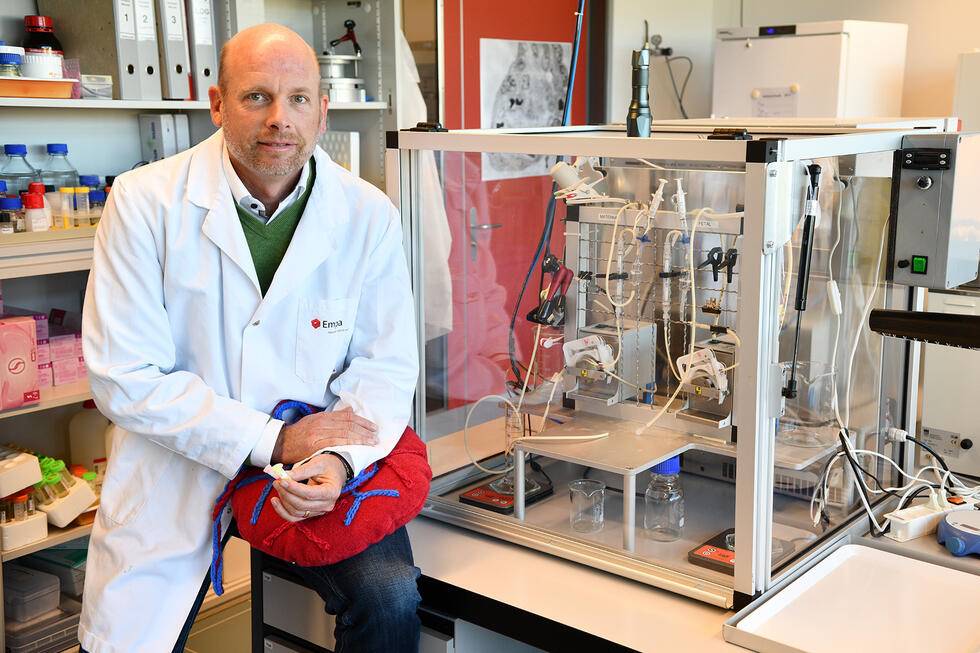

The project is headed by the senior physician Stephan T. Egger. “The idea of visualizing auditory hallucinations is not a new one,” he explains. “But the tools we are using are.” In the past, for example, therapists used a chair on which patients had to imagine a character matching their voice. Then, the therapist would sit outside the patient’s field of vision and imitate the voice. Later, therapists used patient drawings depicting what they imagined the person behind their voice looks like. The therapists would hold the drawing in front of their own face like a mask, thus embodying the hallucinations.

The possibilities of information technology are now expanding these methods, Dr. Egger explains. “Four years ago, I read a study on the use of avatars in treating schizophrenia patients with auditory hallucinations. I immediately wanted to try out what the researchers at King’s College London were experimenting with.” There, however, they only used two-dimensional avatars on a computer screen. Dr. Egger and his team took it a step further: Their avatars are three-dimensional and can be confronted – accompanied by a trained therapist – in a virtual space. This is unique worldwide.

Therapy with a voice modulator and VR glasses

The therapy begins with a preliminary conversation during which patients describe what the voice in their head is saying, which words and recurring phrases it uses. Then the patients reconstruct the voice. The basis is the voice of the therapist, which the patients modify to resemble the voice they hear in their head using a voice modulator. This voice is then used during the course of the therapy. In the next step, the patients create the avatar on a screen using controls and selection menus – in other words, the person they associate with the voice in their head. The therapist then moves to another room, and the patient enters the virtual space using VR goggles. The therapist can make the avatar appear at the push of a button, and can control its face and facial expressions. The therapist talks to the patient via headphones, using the modulated voice. The patients talk to their hallucinations for ten to fifteen minutes. Subsequently, the therapist and the patient discuss the interaction.

Avatar therapy addresses additional sensory levels and generates formative impressions. These can take the place of what previously existed inside the mind of the patient.

Stephan T. Egger explains the benefits: “Avatar therapy addresses additional sensory levels and generates formative impressions. These can take the place of what previously existed inside the mind of the patient. Similar to the way in which images from a movie adaptation of a book overlay what we imagined when we first read the book.” The interaction in the three-dimensional space is controlled by the therapist in such a way that the patient realizes: I can influence the behavior of the voice in my head in a very concrete way. This experience of self-efficacy increases the patients’ self-confidence and in many cases also leads to the voices becoming more benevolent in everyday life, occurring less frequently, or even disappearing altogether. At least, this is what is suggested by the results of the study carried out in England.

Speech transmission is the main challenge

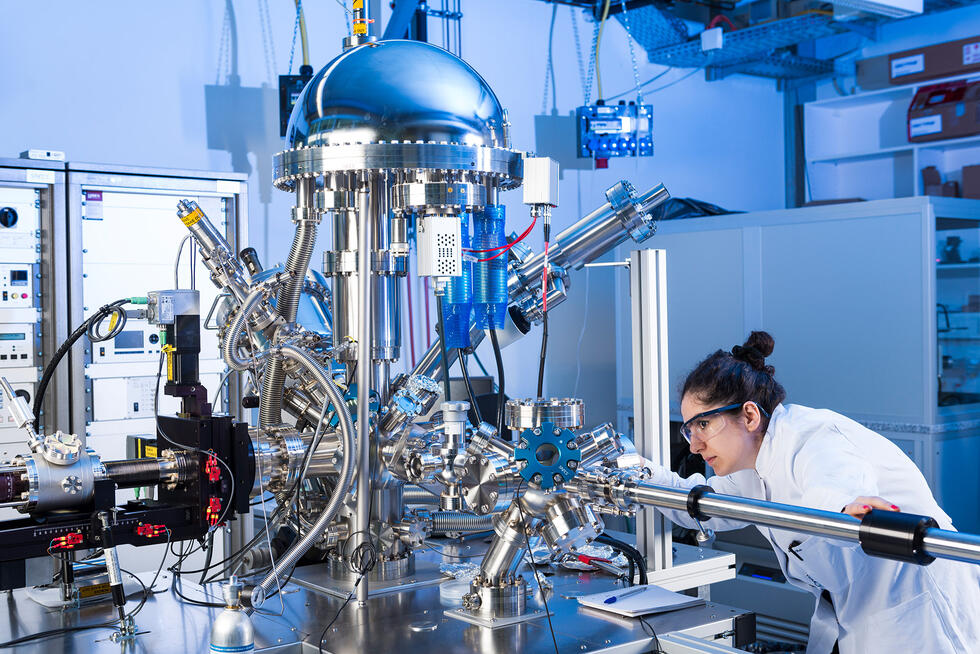

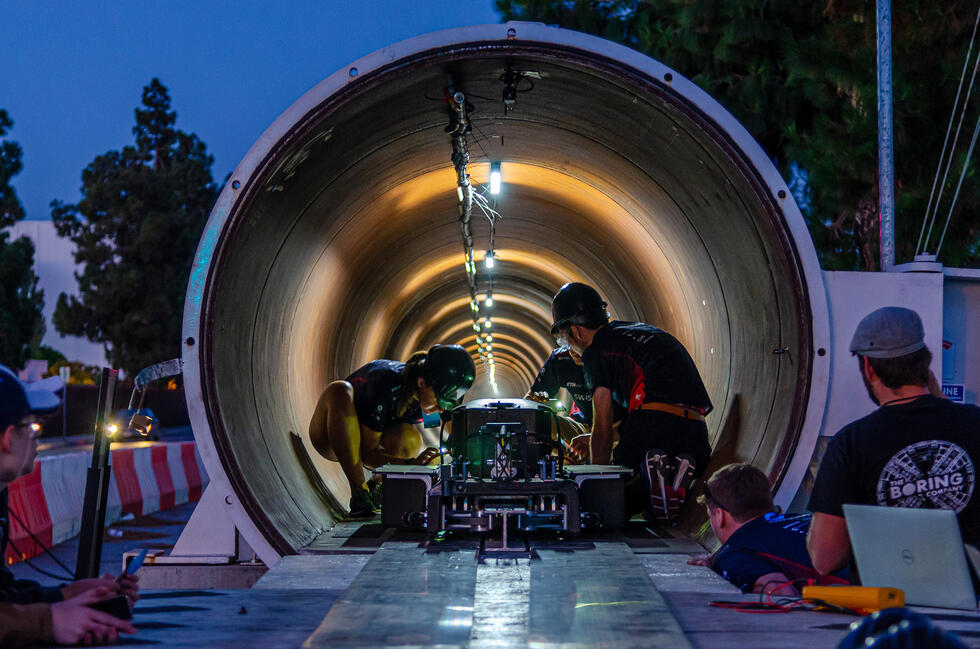

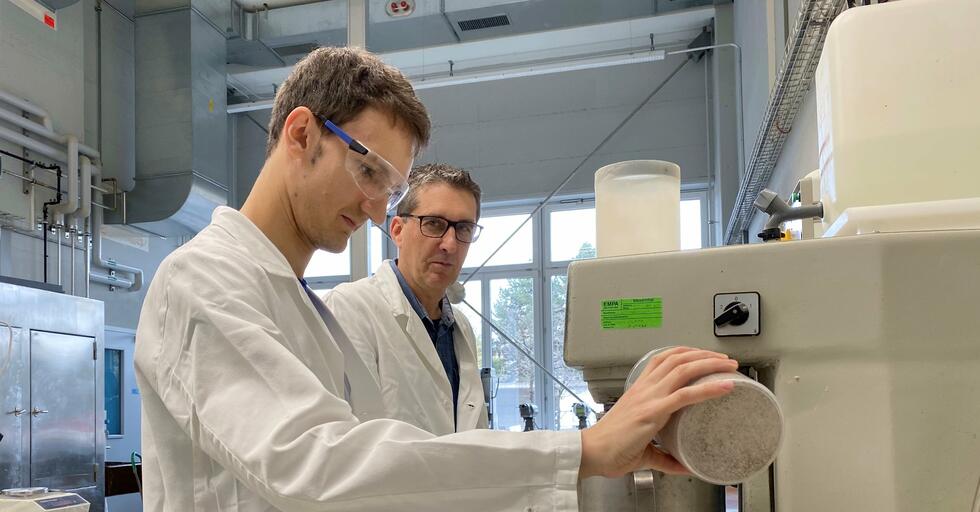

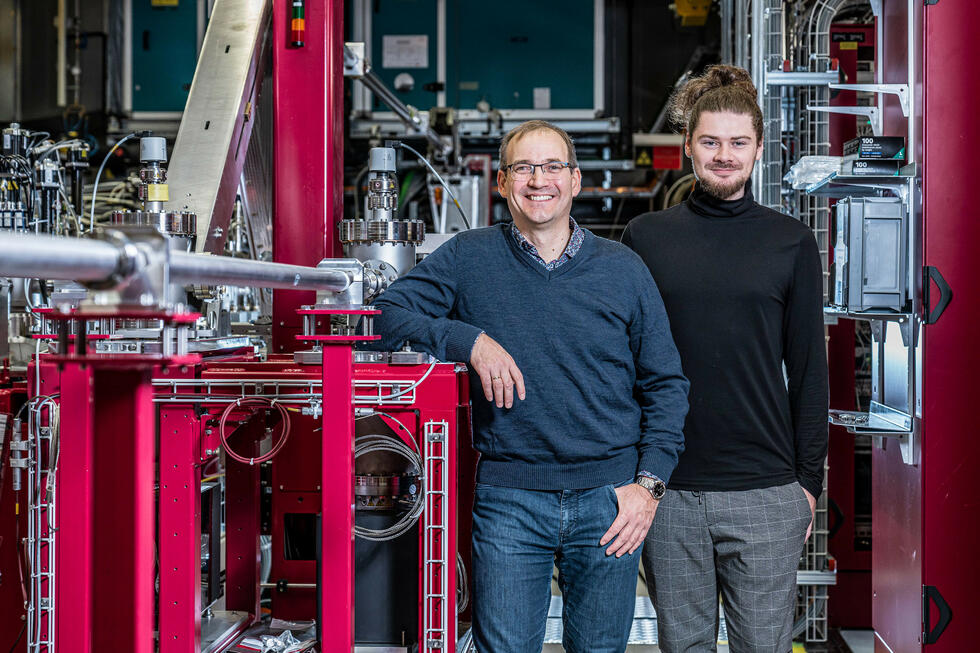

To develop the technology behind the therapy, the University Hospital of Psychiatry Zurich enlisted the expertise of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology’s (ETH) Game Technology Center (GTC). “We research how computer game technologies can be used for other applications,” says Stéphane Magnenat, Deputy Scientific Director at the GTC. “Avatar therapy is a typical example.” Because it brings together various elements that are very familiar to gamers: designing your own game avatar, immersing yourself in the game world using VR goggles, and communicating with fellow players.

In addition to VR goggles, headsets, and the voice modulator, the hardware behind avatar therapy consists of two computers – one for the design of the avatar, and another to control it. The user interfaces for both systems were developed by Mischa Brander from the Game Technology Center. “On the patient side, the main challenge was to provide a sufficient number of options to design the avatar – but not so many that they overwhelm the user,” Stéphane Magnenat says. The developers also placed special emphasis on user-friendliness when designing the control interface, which is operated by the therapist.

The most challenging technical aspect, however, was the communication. Magnenat explains: “The data transfer must take place in real time, so that the patient hears the modified voice of the therapist, who is in another room, clearly and without delay. And the avatar’s lip movements also have to be in sync.” What is more, the developers could not resort to external service providers or servers from large tech companies. “We are operating within a sensitive medical context. Due to data protection requirements, companies such as Google were therefore out of the question,” says Magnenat. “So Mischa Brander developed his own voice-over-IP system and implemented it in a local network.”

Systematically researching the therapeutic effects

The first usability tests have been completed and the developers are satisfied. Over the coming months, Stephan T. Egger and his team will systematically study the therapeutic effect. The focus is on self-confidence: Empowering patients to confront the voice in their head, to control it, and to guide it in a positive direction. Hence, the study focuses on this aspect. Patients are divided into groups and complete both conventional self-confidence training and avatar therapy. The first group starts with one, the second with the other, then they switch. The purpose is to determine whether the key to treating auditory hallucinations lies in self-confidence per se, or whether the self-confidence acquired in engaging with the avatar results in an additional therapeutic effect.

Stephan T. Egger and his team expect the results to be comparably positive to those of the study conducted in England. This in spite of the fact that they are working with a much broader field of patients: Participation in the study is not limited to patients with schizophrenia, but is open to all patients suffering from auditory hallucinations. It is still unclear whether the hallucinations are equally treatable regardless of the underlying disease. “But I am optimistic,” Stephan T. Egger says. “Because thanks to VR and 3D, our avatar therapy addresses even more levels of perception compared to previous methods. This will increase the impact.”

“Because thanks to VR and 3D, our avatar therapy addresses even more levels of perception compared to previous methods. This will increase the impact.”

The senior physician is already considering other fields of application for avatar therapy. For example phobias such as fear of heights or spiders. Here, virtual reality has already been used successfully for several years, he says. “I can also imagine traumatic experiences being processed by means of VR. For example, by re-enacting situations in virtual space and overcoming them.” Avatars could also be a tool for people with social phobias to help reduce fears, develop coping strategies, and build self-confidence. Dr. Egger: “Essentially, we all have our own virtual reality in our heads – our world of imagination. If something goes wrong with it, virtual reality technology can be used, in conjunction with a therapist, to help fix it.”

Photos and written by: