An alpine battleship as a modern data bunker?

There are thousands of military fortifications throughout Switzerland. They used to be a crucial part of the national defense infrastructure, but today they have been repurposed as cheese warehouses, museums, data bunkers – and many are no longer in use at all. But why? On a search for answers in the Furggels fortification, the largest “mountain battleship” in eastern Switzerland.

Switzerland is a landlocked country – and yet it has an ocean-going fleet. Currently, it consists of 17 freighters and two tankers. The combined engine output of these 19 ships tops 13 500 horsepower and in total, they have a cargo capacity of more than nine million metric tons. The ships navigate the world’s oceans, but they are named after places in their homeland. They are called “Bregaglia”, “Lavaux”, or “Lausanne”. This choice of names has a long tradition: The first two of the 14 ships that Switzerland purchased during the Second World War were named “Maloja” and “Calanda”. The purpose of the fleet was to ensure Switzerland’s supply of overseas goods during the war.

Where cows graze next to cannons

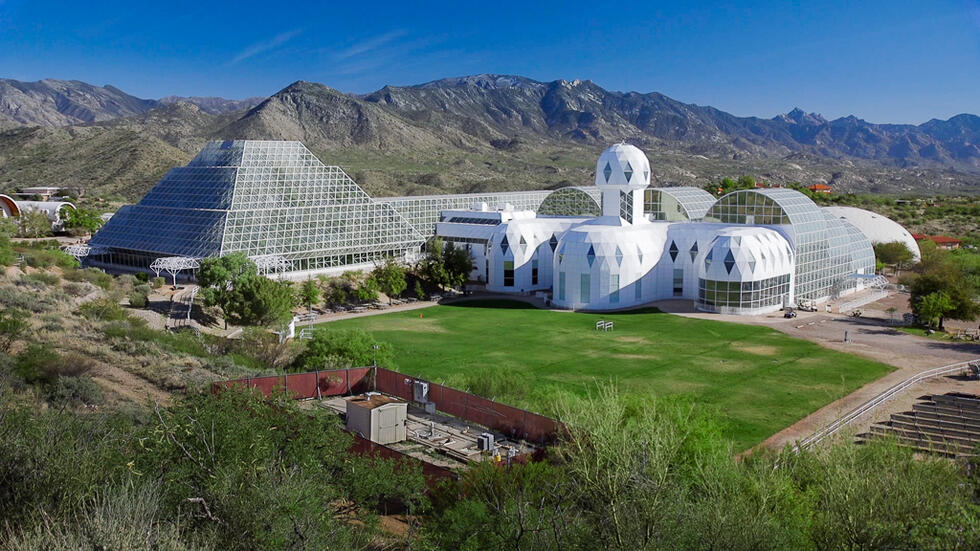

Switzerland is a neutral, landlocked country – and yet it has a war fleet of sorts. However, rather than being sent to roam the oceans or to war, the fleet was built into the mountains. Even today, the three largest fleet units lie deep in the bedrock near Saint-Maurice in the Lower Valais, at the Gotthard in central Switzerland, and near Sargans in eastern Switzerland. The fortifications were built during the Second World War, at a time when Switzerland was building up a merchant fleet to ensure the country’s supply of goods and constructing the famed “Swiss National Redoubt” for national defense.

Like the ocean freighters, these warships bear names associated with Switzerland. The most powerful mountain battleship in eastern Switzerland, for example, is called Furggels. This mountain battleship is anchored in the bedrock high above the villages of Bad Ragaz and Pfäfers. Even higher, in the small village of St. Margrethenberg, the battleship’s armored turrets peek out of the ground. The mighty guns are disguised as stables. Nowadays, the cannon barrels, which protrude several meters out of the stables, are clearly visible. Next to the guns, on the green deck of the Furggels battleship, so to speak, cows graze in summer. These are not part of the camouflage and do not belong to the military, but are owned by local farmers.

The battleship in the bedrock

The Furggels fortification is now privately owned. Erich Breitenmoser bought the artillery complex in late 2018. Anyone who wants to enter the mountain battleship therefore needs an appointment with the Swiss entrepreneur. Then, Erich Breitenmoser drives up the mountain, stops in the middle of the forest in front of what appears to be a board shack and opens the main gates to the fortification. Without him, access is impossible: The fortification is protected not only by its old doors that weigh several tons, behind which are – now unmanned – crenels, but it is also equipped with modern technology; including electronic door locks, surveillance cameras, and motion sensors. Visitors who want to explore the old mountain battleship also need warm clothing. The underground fortification extends over two stories with a total of 190 rooms. The tunnels and corridors have a total length of more than 7.5 kilometers – and the temperature remains at a constant 10 degrees Celsius.

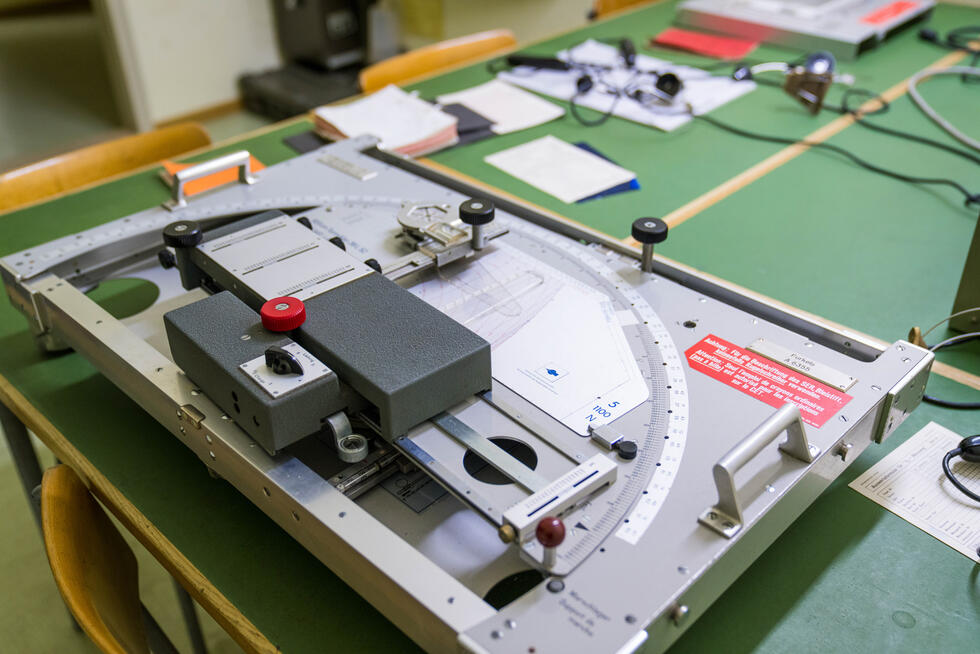

In the past, countless soldiers served in the fortification where Erich Breitenmoser now stands. Even trucks were able to enter the first, cavernous hall via the main access tunnel. The trucks could be rotated using manpower on a turntable, which is still functional today. Behind the cavern, corridors lead to the ammunition warehouses for the tank turrets and the bunker guns. A good ten men were needed to operate a single bunker gun. Whenever one of these projectiles weighing more than 40 kilograms was fired, the window panes in Bad Ragaz far below in the valley would shake. The local spa hotels, it is said, were therefore anything but thrilled when the military would perform their drills with the bunker guns.

In the event of an attack, the Furggels artillery system was designed to prevent enemy troops from entering the Sargans area – in conjunction with other fortifications that were built all around Sargans. Their purpose was to prevent enemy troops from entering Sargans from the north through the St. Gallen Rhine Valley, from advancing westward from Sargans toward Lake Walen, or from advancing eastward toward Prättigau, Chur, and the Grisons Alpine passes. The entire “Sargans fortification” complex was continuously expanded and upgraded over a period of several decades. In 1998 however, due to the Military Reform 95, the Furggels fortification lost its classified status – and like thousands of other military facilities, it was no longer to play a role in Switzerland’s defense.

A fortification instead of a couple of sports cars

But the fortification still appears to be fully operational. From the massive cannon in the casemate to the cooking pot in the canteen and right through to the notepad in the command post, everything still looks like it used to. You almost expect the telephone on the wall to ring and to hear a harsh order barked through the receiver. In the gunnery office, you can imagine the murmur that used to accompany the calculations of the projectile’s trajectory. After all, there were no computers here. Instead, the fortification boasted a hospital with three decontamination stations, a command office, a workshop, a fuel reservoir with a capacity of around 200 000 liters, and a 1.8 million liter water reservoir – all of which are still here today. In the event of an emergency, the crew of 420 could have held out inside the Furggels fortification for months on end. More than 500 beds were available for officers, non-commissioned officers, and troops. In addition, there was a bakery, various food storage rooms, a large central kitchen, and several canteens. As well as a military post office, a laundry, sanitary facilities, arrest quarters, and even a mortuary...

Why would anyone buy such a gigantic fortification? This question usually elicits a dry answer from Erich Breitenmoser. Others might have used the money to buy a holiday cottage or a sports car or two, he says. He simply decided to spend it on something different. However, the 60-year-old entrepreneur is not so much interested in cultivating an extravagant hobby as he is in preserving Swiss cultural heritage. And this is truly a rare piece of military history: Furggels is the largest privately owned Swiss fortification. Erich Breitenmoser will not disclose how much he paid for it. At least he reveals this much: The electricity bill alone amounts to 1800 Swiss francs a month.

some 2000 military buildings and facilities have been sold or given away on a leasehold basis since the 1990s

2000 military buildings have already vanished

But what has happened to all the other bunkers and fortifications that were decommissioned during the course of the Military Reform 95? And how many changed hands? “All in all”, says Kaj-Gunnar Sievert, “some 2000 military buildings and facilities have been sold or given away on a leasehold basis since the 1990s”. Kaj-Gunnar Sievert would know: He is Head of Communications at Armasuisse, the Federal Office of Armaments, which is responsible, among other things, for the Defense Department’s real estate. What the communications specialist cannot divulge: How the decommissioned bunkers and fortifications are used today. Armasuisse does not keep records on this.

It is known that the former ammunition depot at the foot of the Blüemlisalp, the massif in the Bernese Oberland, is now used to store cheese. And the former San Carlo artillery facility on the Gotthard mountain pass is now being used as a wellness hotel. And it is also no secret that various companies offer storage space in former military bunkers – for digital data, gold bullion, or works of art. However, it is less well known that repurposing military buildings is not entirely straightforward. “90 percent of Switzerland’s defense facilities are located outside of building zones,” says Kaj-Gunnar Sievert. This means: Permits for redevelopment are hard to come by. Unless a facility is listed as a heritage site and meets the requirements of the Spatial Planning Act (RPG Art. 24).

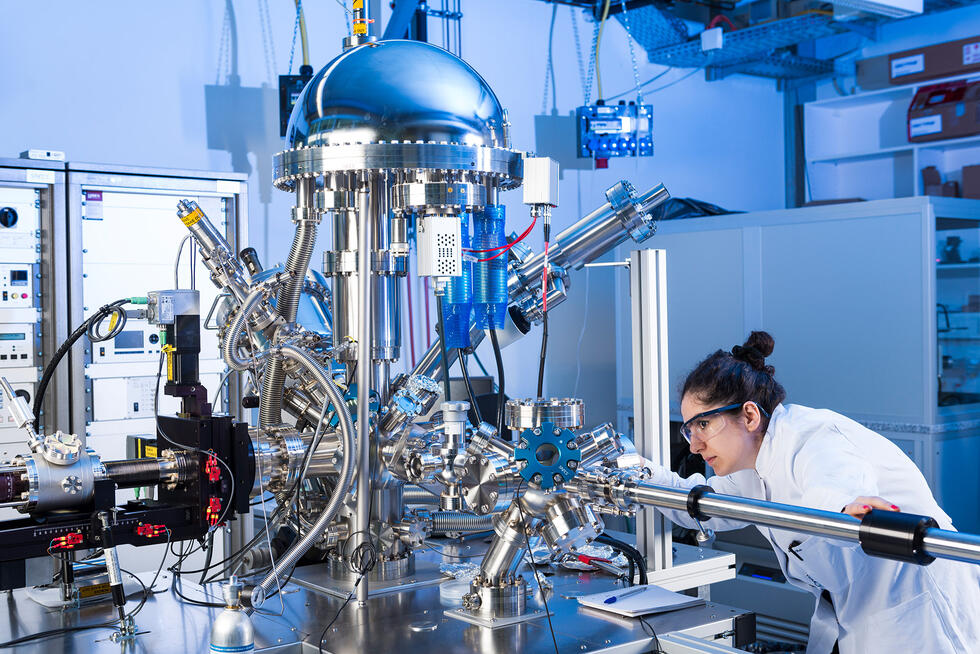

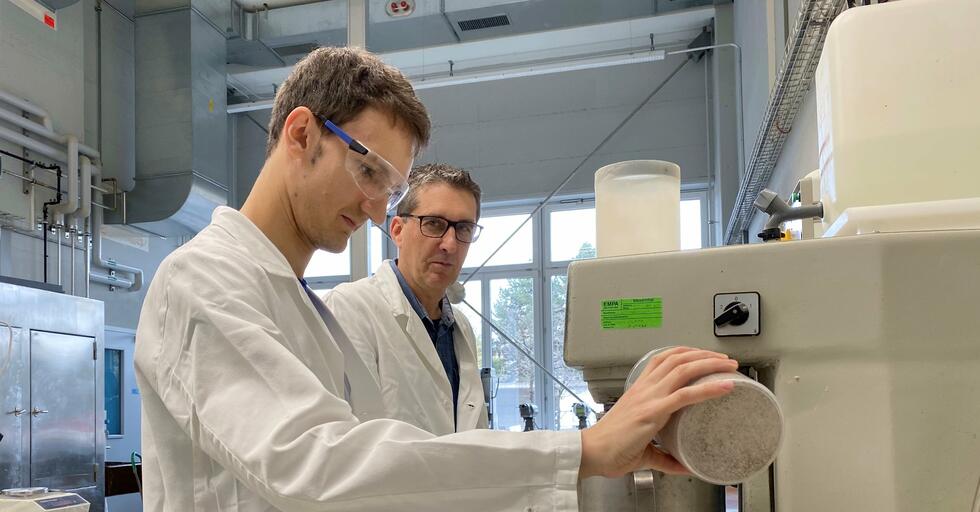

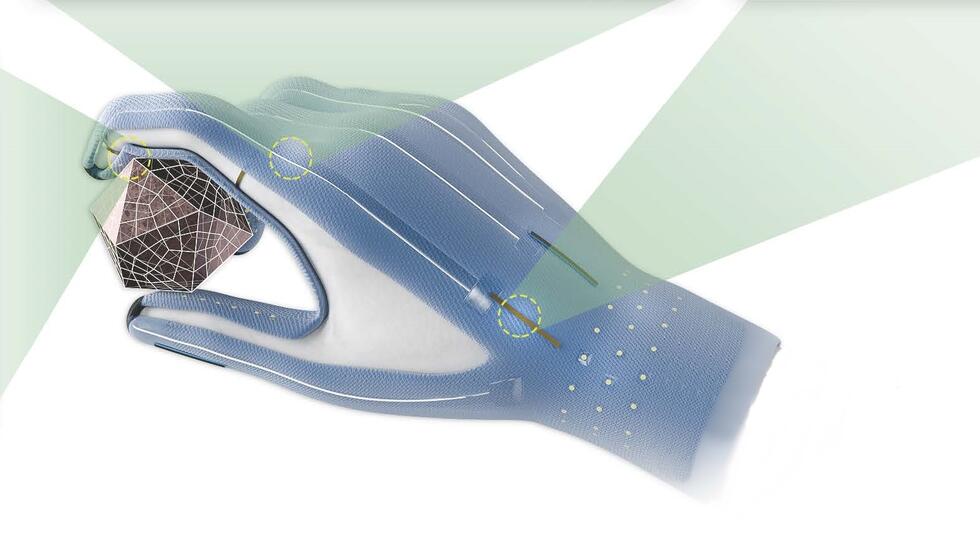

This was the case with Furggels: In 2009, an innkeeper bought the fortification to conserve it for future generations. Then a godchild of the innkeeper took over this task – and now it is Erich Breitenmoser’s turn. However, the preservation and repurposing of the fortification are not entirely mutually exclusive. The Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich has leased two rooms in Furggels. Deep inside the mountain, sealed off from virtually all environmental influences such as noise, vibrations, or electromagnetic fields, the university is currently conducting experiments to research the interaction between vibrations and gravity.

For whom the doors open

Erich Breitenmoser intends to open up his fortification to additional tenants. He sees plenty of potential, if only because the fortification can be used to safely store the goods that make up the largest corporate assets in terms of volume: data. The storage facility is bombproof, the entrepreneur explains. It could even survive a nuclear attack. And on his website, he promises: “All your data will be housed in a super-high-security private server located in Switzerland. That means you’ll have your own private cloud inside a Swiss mountain that is bullet proof. It’s also nuclear proof, meaning it’s so secure no major disaster or war will affect its contents.” There is a reason why Erich Breitenmoser touts the advantages of data storage in English: He lived in California for many years, earning his living as “Dr. Erich”, a chiropractitioner, a coach for other professionals in his field, and a supplier of associated handbooks, tools, and seminars.

In the United States, Erich Breitenmoser also came into contact with “preppers”, people who do not believe that the public infrastructure will offer them protection in the face of war, a pandemic, or a natural disaster. And how do preppers try to protect themselves from crises and catastrophes? Naturally: They prepare for survival in a bunker. Accordingly, Erich Breitenmoser has already received inquiries as to whether it would be possible to weather the Corona pandemic in his “Swiss mountain fortification”. Unfortunately, it is not possible to offer a hotel service, Erich Breitenmoser had to reply. For data storage, however, his doors are open – and will lock securely behind the data he is entrusted with. After all, they were designed to keep out chemical warfare agents and to withstand the shockwaves of explosions...

Postscript: Referring to artillery sites as battleships in this article may raise the question of whether the Swiss Armed Forces have a navy. They do not. But they do have almost a dozen patrol boats.

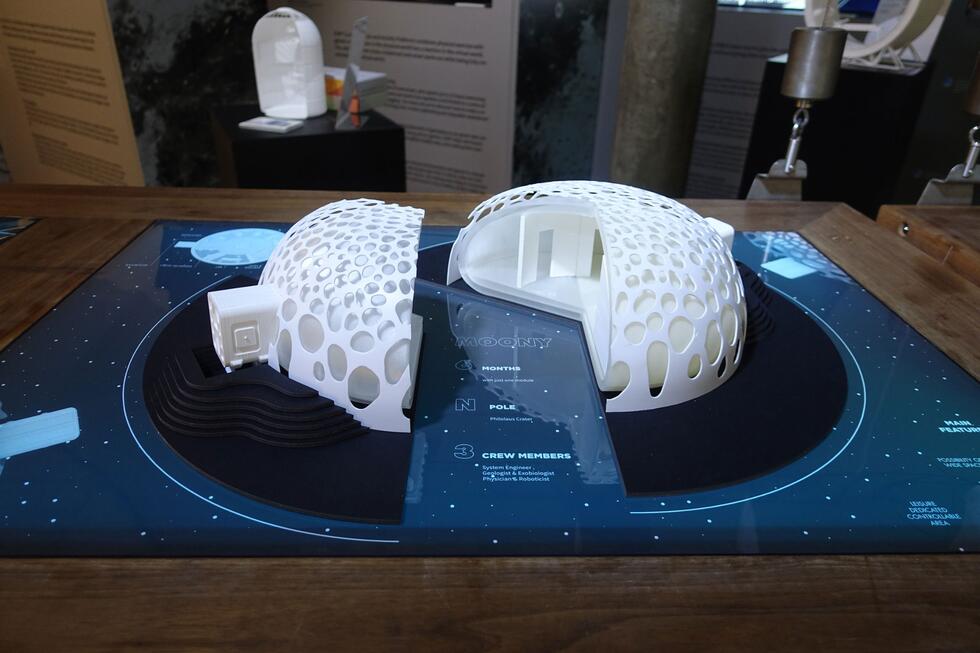

Gallery of "The Secret Swiss Underground Fortress"

Big data in the bunker?

Can data be safely stored in former military bunkers? The reply of several Swiss companies is a clear yes. The Swiss government is somewhat more skeptical, even though it constructed the bunkers in the first place. What are the challenges?

The name is reminiscent of a codename for a secret organization in a spy story: Bureau for Fortification Buildings. However, this department, referred to as BBB for short, was in operation even before the heyday of Cold War espionage: Starting in 1935, the BBB planned the construction of hundreds of military facilities on behalf of the National Defense Commission. The BBB already existed between 1886 and 1921, and its second life ended in 1951 when it was incorporated into the Swiss Armed Forces’ newly founded Department of Engineering and Fortifications.

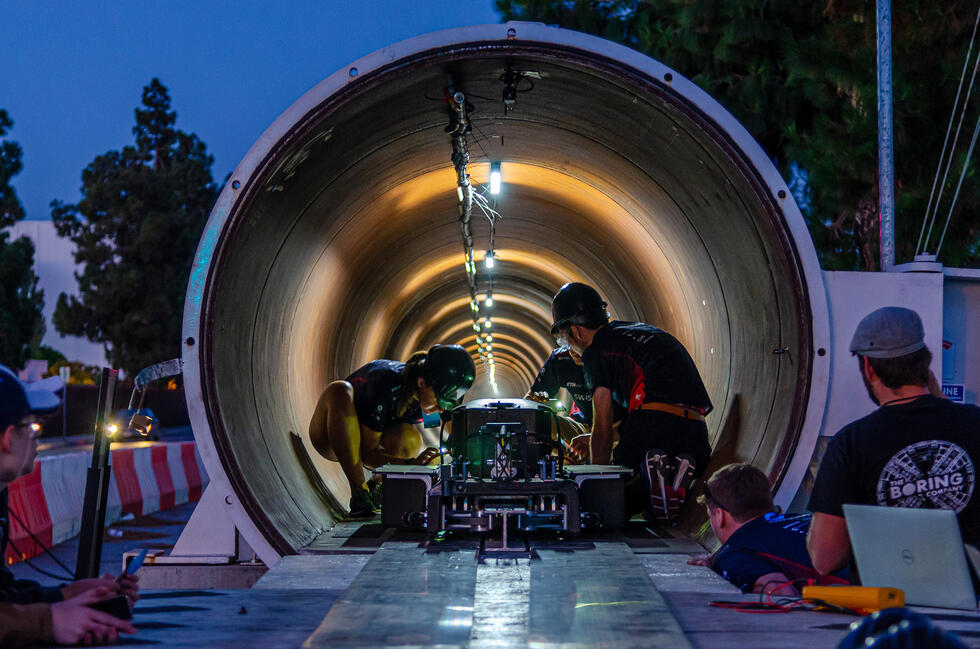

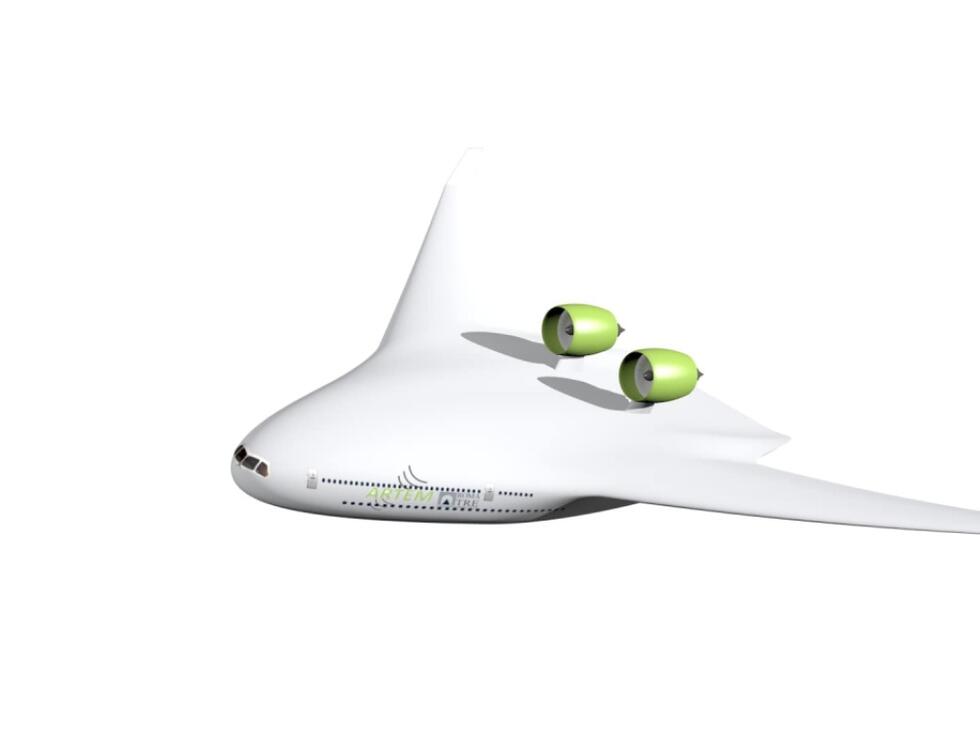

Historically, Switzerland can thus draw on many years of expertise in the construction, operation, and maintenance of fortifications and smaller bunkers. However, since the end of the Cold War – and thus since the recognition of changed threat scenarios – the country has found it difficult to find new uses for its old facilities. More than 2000 properties of different sizes have been sold over the past 30 years, and in 2019 alone, 190 bunkers, anti-tank barriers, and other facilities changed hands. But thousands of sites – both known and secret – are still owned by the federal government. At least two fortifications are now to be repurposed within the Armed Forces: The Defense Department plans to establish three large, secret data centers. Two of these, at least it is believed, will be constructed within existing bunkers.

Written by: Thomas Kaiser

Photos: